Sarah E. Goode is the name of one of the first African-American women ever to be granted a U.S. patent, in 1885, for a foldout bed that converted into a desk--a prescient object that would fit right into a modern-day Ikea catalog. It's also the name of a new high school on Chicago's South Side that is redefining what it means to be educated in the 21st century.

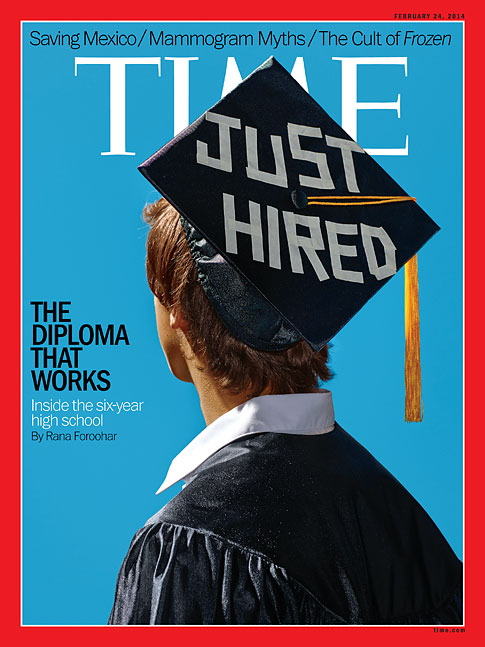

Kids at the school, which launched a year and a half ago, aren't called students but "innovators." They receive a hardcore focus on STEM skills (that's science, technology, engineering and math). And they take six years to graduate instead of the traditional four; the extra two years means they walk away with an associate's degree on top of their high school diploma.

There's one more thing they take with them: a job. Every student at Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy graduates with a promise of a $40,000-plus opportunity at IBM, the school's corporate partner and a key developer of the curriculum. A place in this school, which rises gleaming and new in a neighborhood littered with dingy bail-bond shops, check-cashing places and fast-food joints, is very likely a ticket to the middle class.

Stanley Litow, IBM's vice president of corporate citizenship and corporate affairs, helped start this school and seven others like it in New York and Chicago. With 29 more such academies set to open in two states over the next two years, he's part of a mission to do nothing less than reinvent American secondary education. Litow launches into an orientation speech for ninth-grade students as if he were talking to a valued client, thanking the kids for choosing Sarah E. Goode. He tells them that IBM has a big stake in their success--as does President Obama, who for two years running has heralded such schools as a model for the nation in his State of the Union speech. "We need people who look like you, sound like you, live like you and have your aspirations," says Litow, echoing the President's call for a new 21st century workforce, one that's not only better skilled but also more diverse and inclusive. The kids, African American except for a handful, burst into applause as he finishes. Then they file off quickly to class, past a welcome innovators sign, while a soundtrack of motivational rap and dance tunes (Public Enemy, TLC, Calvin Harris) plays in the background.

Despite Chuck D's musical entreaties to "fight the power," these kids don't seem like revolutionaries; they just seem grateful to be given a chance to excel in a school that has no test-in exam or steep tuition and where educators seem genuinely happy to serve them. But like Litow, their teachers and everyone else at Sarah E. Goode, these teenagers are part of a major new experiment in American education. If successful, this kind of school could help power the sort of great national leap forward that hasn't happened since the post--World War II period, when state governments decided that high school, previously optional, should be mandatory, in order to ensure the kind of skilled workforce needed to compete in a new, higher-tech industrial era.